Having raised over half a million dollars in 25 days on Kickstarter, Robot Turtles founder Dan Shapiro has been featured in major print and online publications, including the New York Times, NPR and Techcrunch. Not only did he soar past his $25,000 crowdfunding goal by more than 2500%, he also delivered the perks he promised to backers earlier than expected.

Where most Kickstarter creators struggle with shipping rewards out on time and dealing with unpredictable levels of demand, Shapiro was able to scale his original plan, execute on his vision, and successfully navigate the choppy waters of product fulfillment to both domestic and international backers.

In our interview with Shapiro, we’ve given you an inside view of a smash-hit six-figure Kickstarter project and how a small project turned into a thriving business.

How did you come up with the idea for Robot Turtles as a board game?

I was tired of kids’ board games that were thinly veiled luck or games of skill in which the kids were hopelessly outmatched. I wanted something that would afford real quality time with my then four-year-old twins. And I wanted some of that cool “A-ha!” discovery that is so fun to watch.

What was your kids’ initial reaction?

They got it immediately. Their first reaction was to tell me how I should improve it: “Daddy, I don’t like that wall. I want lasers!” or, “Daddy, I want to play more than just one card at a time!”

Why is it called “Robot Turtles?”

The game is very loosely based on a programming language called Logo that I learned in computer camp in the early 1980s. Logo features a turtle character that players, using the Logo programming language, send around the screen to draw pictures.

Why did you choose to crowdfund and who were you targeting?

I could have self-funded a small print run, but then I’d be stuck with a thousand games in my garage. And if it turned out that nobody wanted the game, what then? Kickstarter was the best way to find out if people truly wanted the game to exist so I’d know if I was wasting my efforts before starting manufacturing.

What made your Kickstarter video a success?

I don’t really know, but I think it has to do with the concept more than the game. People never got to try the game before they pledged. It’s lots of fun, but they had no way of knowing that. I think the backers had an intuitive sense that this was something worthwhile.

Programming concepts like order of operations and decomposing complex actions are basic elements of thought—things that kids tend to be really good at. Why should they have to wait to learn to read to start exploring these skills? That resonated, and people got excited about seeing what a product like that could be.

I think crowdfunding campaigns work best when they describe something to the world that people want to exist. If it’s a good idea, people will get excited about it. It also helped to email, tweet, and post on Facebook to get the ball rolling.

Did anything happen during the crowdfunding phase that you didn’t anticipate? How did you respond?

I was bowled over by the enormous reception. It was fully funded in five hours and at four-times my goal in two days and then never stopped. From the moment it fully funded, I switched into overdrive reviewing all my production plans to see if they would hold up under the strain of a much larger order.

What challenges did the excessive funding present post-campaign?

Everyone’s expectations were high. I tried to be incredibly communicative, sharing pictures and updates, so everyone had 100% transparency. Ironically most overfunded crowdfunding campaigns are very late, but I shipped a smidge early. I think that bought me a lot of breathing room with my backers for the snags that did come up, such as lost packages.

How quickly did you shift to order fulfillment, and were you able to meet the holiday orders?

The manufacturing process started the day the Kickstarter campaign closed. I had a schedule with two weeks of buffer to get product to U.S. addresses in time for Christmas. I wound up getting it out about one week before Christmas. There were a few delays, but Delano Services, my manufacturer, stepped on the gas and made up the time by finishing early.

How did you get your first non-Kickstarter customers?

I sold out the remaining inventory in a month or two through the product’s website: www.robotturtles.com.

Are you still printing copies of the game?

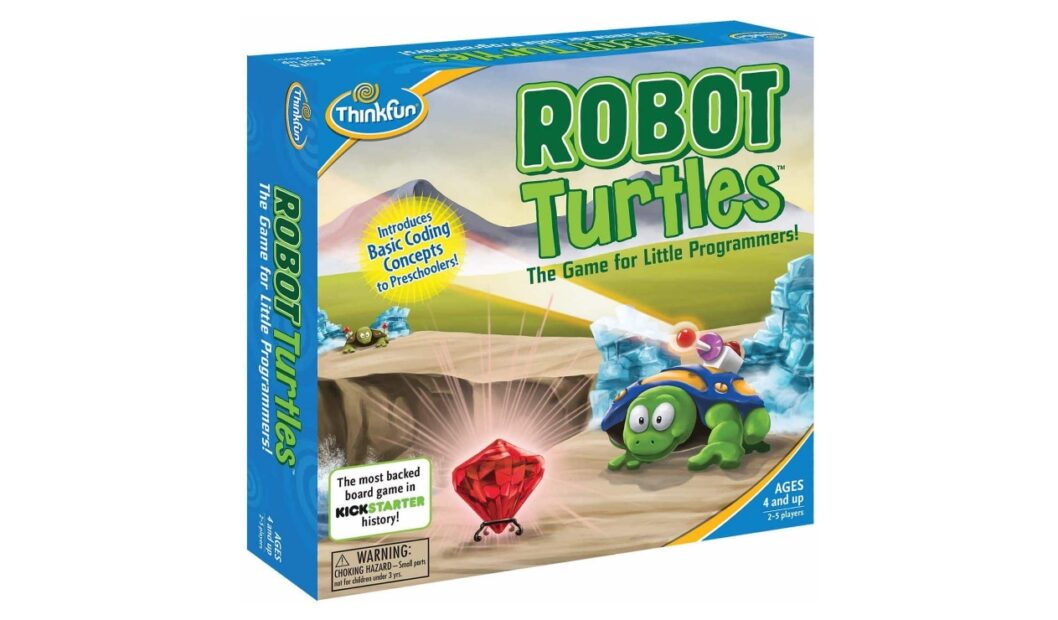

No, I’m done. But Thinkfun, an amazing manufacturer of kids’ board and educational games, has started. They’re producing a version of the game that’s very similar but with a few great improvements, such as shiny gold highlights on the pieces and a nicer box and manual. You can buy it now at Target and Amazon.

What happened post-Kickstarter with regard to operations, such as staffing, changes to tactics or strategy, struggles, and successes?

There’s not much to report. This is a one-man show with some amazing contractors helping out with design and support. I just worked like mad to get everything out for the holiday, breathed a big sigh of relief, and turned over manufacturing to Thinkfun who’s done a tremendous job with it.

When did you develop the e-book?

My friend, Brad O’Farrell, the creator of Story Wars, helped me write it during the campaign. Then the same designer who designed the game illustrated it after the campaign closed.

Did anything occur during the first year that you didn’t anticipate? How did you respond?

Just one huge hiccup: I was planning on using Amazon for fulfillment, but they miscommunicated about their ability to fulfill overseas orders. I was left with nearly 2,000 international game orders and no way to get them out for the holidays. Fulfillrite jumped in and saved my bacon—sitting on the phone with me until the late hours in order to get the process squared away and rushing the packages out the door. I would have been in deep trouble without their help.

What are your plans going forward?

I’m working on a book about startup CEOs for O’Reilly Media and enjoying the Seattle season.

To read more about what it’s like to launch and run a successful crowdfunding campaign, be sure to check out the rest of interviews in this series LINK.

The game is very loosely based on a programming language called Logo that I learned in computer camp in the early 1980s. Logo features a turtle character that players, using the Logo programming language, send around the screen to draw pictures.